POLITICAL COMMENTARY, SATIRE: A POLITICAL STAPLE LONG BEFORE KIMMEL

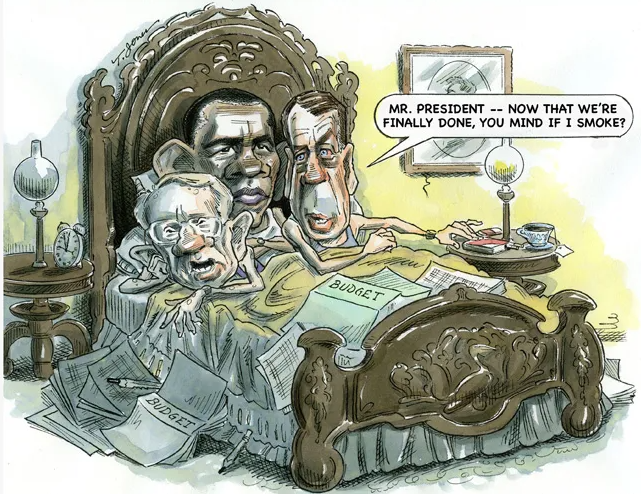

Caricature artist Taylor Jones is known the world over for capturing the essence of current events, news stories and the cast of characters within. He is the former illustrator of the ‘Washington Whispers’ page of U.S. News & World Report, and the author of Add-Verse to Presidents, a satirical look at the presidency from Washington to Reagan.

The Integrity Project

Thanks to the First Amendment, the ability to parody U.S. Presidents dates back to our earliest days. “To receive the adulation of the public, those entrusted with the power of the people must also be able to accept criticism,” second U.S. President John Adams said. He also wrote that, “the jaws of power are always open to devour…freedom of thinking, speaking, and writing” and that the scrutiny of those in power is necessary for liberty to be preserved.

Before the advent of broadcast media, and long before the recent clash between the White House and late-night host Jimmy Kimmel, political satire occurred in the pages of periodicals like the National Gazette, which was critical of George Washington's administration; Ben Franklin's Aurora, known for its harsh criticism of Washington and Adams; and the Harvard Lampoon, which has a history of poking fun at presidents since the 1870s. The Lampoon parodied early U.S. presidents through cartoons, irreverent covers, and humorous depictions that satirized Presidents’ character, policies or actions.

An early Lampoon cover exaggerated the large persona of Theodore Roosevelt, a pattern that would recur with other presidents like John F. Kennedy, Richard Nixon and others. These parodies often focused on personality traits, referenced current events, policies, and employed tongue-in-cheek humor typical of the magazine’s broader style. Needless to say, Presidents have varied widely in opinions as to whether such efforts were in good humor or something more nefarious.

Presidents that famously pushed back against satire included Andrew Jackson and Richard Nixon, who took the commentary far more personally and sought revenge; while others like Lyndon Johnson, who was a frequent target of The Smothers Brothers comedy duo, chose to absorb the criticism, even thanked them, recognizing the commentary as part of democratic discourse. Modern Presidents have even chosen to participate in parodies of themselves, perhaps most famously in the context of Saturday Night Live.

Jackson’s presidency took a uniquely combative approach to satire: he received ferocious public and personal attacks, and responded with equal intensity, making him the subject of some of the most iconic political satire in American history. Jackson pushed back both publicly and privately, directing loyalists to defend his reputation, authoring anonymous pro-Jackson editorials, and shaking up Cabinet positions as retribution during a battle with the Bank of the United States and Cabinet in-fighting which was ultimately crushed by Jackson when he sent his entire Cabinet home, excluding Postmaster William T. Barry, and replaced them with loyalists.

And Richard Nixon did not simply endure satire — he developed a deep resentment toward the media, comedians, and critics, believing in a conspiracy against his reputation. His private tapes and writings reveal his sensitivity to how he was mocked, and his administration placed several political enemies, including journalists and satirists, on an “enemies list” that led to IRS audits, termination of grants and other forms of harassment.

While Nixon may not have filed direct legal action against perceived enemies, his team used the machinery of government to order investigations to intimidate critics, manage press coverage and push the boundary of Presidential power. He ordered the wiretapping of journalists, government employees and scholars suspected of leaking information, such as policy advisor Morton Halperin, who had his phone tapped for 21 months by the FBI despite no evidence of wrongdoing. He infamously directed a special unit called “the plumbers” to break into the offices and homes of critics to dig up evidence of malfeasance, famously leading to the Watergate scandal – and his ultimate downfall.

Humor about serious and controversial topics is not uniquely American. But in America it is uniquely protected and should be cherished as a treasured feature of our discourse.

ADDITIONAL NEWS FROM THE INTEGRITY PROJECT