Rewriting the Past: Oklahoma’s Social Studies Standards Echo Historic Misinformation Campaigns

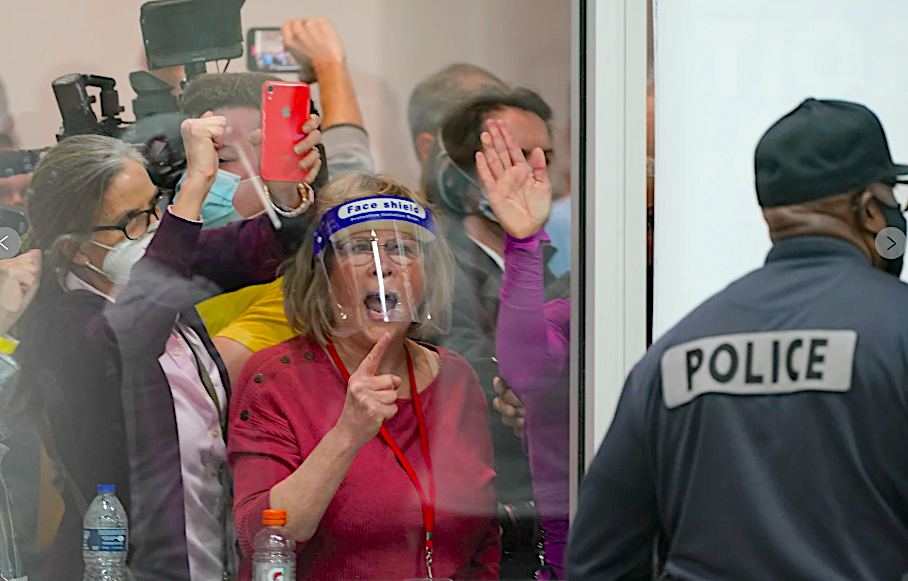

Election challengers in Detroit yell as they look through the windows of the central counting board in November 2020. Photo by The Associated Press

The Integrity Project

In late February, Oklahoma State Superintendent Ryan Walters presented the State Board of Education with a 400-page revision of the state’s social studies standards—just hours before a scheduled vote. The changes, which included highly politicized revisions about the 2020 election and the COVID-19 pandemic, blindsided board members and ignited bipartisan criticism from lawmakers and educators across the state.

Board members received the updated standards via email at 4:01 p.m. on Wednesday, February 26. Less than 24 hours later, they were asked to vote. New board member Ryan Deatherage immediately objected to the rushed timeline and requested a delay.

He wasn’t alone in his concern. Board member Michael Tinney later admitted he assumed the vote was for the original December draft—the only version posted on the Education Department’s website at the time. “It never dawned on me that it could change without telling the board,” Tinney said.

Asked to produce documentation justifying the revisions, Walters dismissed the request: “First of all, it’s a completely irrelevant part of the conversation…I make the decision on what’s in the standards and what’s not.”

Walters Confirms Post-Public Comment Changes—But Not the Process

When pressed by board members, Walters confirmed: “Absolutely there were changes made after it was paid for public comment.” Yet he dismissed concerns about transparency and timing, stating, “I can’t make you read. I can’t make you do the research before you vote.”

Walters insisted the rush was necessary to meet a legislative deadline—but state law only requires the standards be submitted “prior to the last 30 days of the legislative session,” giving the board ample time to deliberate. “I am highly disappointed that I was misled in that meeting,” said Deatherage. Despite the objections, the board voted 6-1 to approve the standards. Deatherage was the lone dissent.

The altered standards removed references to bipartisan infrastructure efforts and economic recovery during the Biden administration and added lines emphasizing Trump-era policies. They also introduced unverified claims about the 2020 election—such as “batch dumps” and “contradictions of bellwether counties”—as well as the disputed theory that COVID-19 originated in a Chinese lab.

On the reasoning for the changes, Walters has been quoted as saying: “The left has been pushing left-wing indoctrination in the classroom. We’re moving it back to actually understanding history…and I’m unapologetic about that.”

Rep. Ronny Johns (R-Ada), a former educator, criticized the politicization of the standards. “Teachers have to remain neutral. You're opening up an opportunity for teachers to insert their biases,” he said.

House Common Education Chair Rep. Dick Lowe (R-Amber) echoed the concern: “Now I kind of even more understand where the new board members had some reservations, because I’m not sure they had a chance to see all this.”

Lawmakers had the power to reject or send the standards back for revision. Governor Kevin Stitt supported returning them to the board, as did half of the state education board. But the Republican-controlled Legislature declined to act—effectively allowing the new standards to become law.

Sen. Mark Mann (D-OKC), a member of the Senate Education Committee, was blunt: “This is a mess. When you start deviating from what is the norm and the truth, there’s going to come a point where Oklahoma won’t have a textbook publisher willing to align to our standards.”

History of Successful Misinformation in Schools

In reality, every credible review—state, federal, and journalistic—has confirmed that the 2020 election was among the most secure in American history. Theories about a Wuhan-lab releasing COVID-19 are still debated and not accepted fact. To mandate instruction otherwise is the state-sponsored codification of debunked conspiracy theories as civic truth.

This raises a critical question: Can this sort of misinformation take root in the American classroom and influence future generations? Or will it ultimately fail, in a society that values liberty and pluralism?

History suggests that we should be cautious about assuming such efforts will fail. The United States unfortunately has a long track record of ideological narratives—many of them rooted in misinformation—being successfully embedded in public education and lasting for generations. These narratives haven’t been permanent. Over time, and often only through sustained civic, legal, and educational pressure, they’ve been challenged and replaced. The process is slow and hard-won, but it demonstrates that misinformation, once entrenched, can be uprooted—if the will to confront it exists.

The Lost Cause: A Long History of Successful Misinformation in Schools

Perhaps the most enduring example is the "Lost Cause" myth; the romanticized retelling of the Confederacy's motives in the Civil War. From the early 20th century well into the 1980s, textbooks across the American South taught children that the war was about “states’ rights,” not slavery, and that Confederate generals were noble defenders of liberty.

This wasn’t incidental. Groups like the United Daughters of the Confederacy explicitly lobbied textbook committees, wrote curriculum guides, and pressured school boards to adopt only “approved” historical texts. In Mississippi, a 1974 study found that public school history books portrayed slavery as benign and black Americans as passive. The state only adopted more accurate materials after a 1980 court ruling compelled them to do so.

This system of misinformation didn't collapse on its own. It was protected by local officials, deeply embedded in teaching practices, and ultimately dismantled only through sustained legal and civil rights pressure. In short, it worked—for nearly a century.

Cold War Education: “Americanism vs. Communism” in the Classroom

Another case study comes from the Cold War era. In the 1950s and ’60s, fear of Soviet influence led to widespread mandates for anti-communist education. Florida required all high school students to take a course called “Americanism vs. Communism,” designed not to encourage debate but to enshrine one worldview as correct.

These programs were less about intellectual freedom and more about enforcing ideological loyalty. Critics at the time noted that these lessons stifled classroom discussion and created a chilling effect on teachers. Yet the curriculum remained in place until the early 1990s, long after the Cold War had ended. Again, the initiative was not undone by widespread public resistance—it faded only when the geopolitical threat that justified it receded.

Revisionist Narratives on Native American History

Throughout much of the 20th century—and in many cases still today—U.S. public education has sanitized or distorted the history of Native Americans, particularly regarding colonization, forced removal, and genocide. Textbooks routinely depicted European settlers as heroic pioneers and downplayed or entirely omitted the violence inflicted on Indigenous peoples.

For example, the narrative surrounding Manifest Destiny was often taught as a natural and righteous expansion of American civilization, rather than a policy that resulted in mass displacement and cultural destruction. The Trail of Tears was typically framed as a “tragic but necessary” consequence of progress, not as an act of ethnic cleansing enabled by federal policy.

It wasn’t until civil rights activism, academic pressure, and growing public awareness in the late 20th century that curricula began to shift—though even today, many states still struggle to include in them comprehensive, honest accounts of Native American history.

Change Is Hard—But Possible

The controversy surrounding Oklahoma’s new social studies standards is not just a dispute over curriculum—it is a test of democratic accountability and historical memory. By bypassing transparency and embedding partisan narratives into public education, Superintendent Walters has set a troubling—but familiar—precedent: one in which ideology overrides evidence, and public oversight is treated as optional. History warns us that such efforts can succeed if left unchallenged.

From the Lost Cause mythology to Cold War indoctrination and white-washing American history with Indigenous tribes, misinformation in classrooms has often endured longer than the crises that inspired it. If Oklahoma fails to confront this moment with the seriousness it demands, it risks repeating a pattern in which political expediency trumps educational integrity—and students bear the cost for generations to come. But history also reminds us that these patterns can be broken—when communities speak out, demand better, and insist that public education serves truth, not ideology.

LEARN MORE ABOUT THIS TOPIC FROM THE EDITORS OF THE ASSOCIATED PRESS

ADDITIONAL NEWS FROM THE INTEGRITY PROJECT